Chapter 2: Background

At a high level, the production of dairy farming and livestock can be expressed as the result of a phenotype product \(P\) which is a combination of a genotype \(G\) realization and environmental factors \(E\): \(P = G + E + G \times E\) (Citation: Adhikari et al., 2022 Adhikari, M., Longman, R., Giambelluca, T., Lee, C. & He, Y. (2022). Climate change impacts shifting landscape of the dairy industry in Hawai‘i. , 6(2). txac064. https://doi.org/10.1093/tas/txac064 ). The genetic factors \(G\) are influenced by breeding. The environmental factors \(E\) are farm management practices such as housing or feeding, policy and socio-economic environment, ambient weather and climate. Both breeding strategies and changing environmental conditions impact susceptibility to heat stress, dairy performance, animal health and reproduction. The interaction between the \(G\) and \(E\) determines to which degree a dairy cow may express the full genetic potential with respect to a selected metric such as milk performance.

Given the animal-level nature of our dataset, this chapter starts with an overview of the physiological aspects of dairy cows under heat stress conditions in Section 2.1. We thereby highlight critical factors that may necessitate modelling. Then, in Section 2.2 we analyze a range of selected models estimating heat-effects across breeds to appraise the current technical state-of-the art and identify potential gaps. This is followed by a comprehensive review of the developments in Swiss milk production over the past four decades in 2.3, aligning with the scope of our data: breeding associations set long-term goals which ideally increase the milk yield in the long run. Moreover, legislative amendments and policy measures can substantially influence farm management practices and breeding techniques. Collectively, this chapter establishes the foundational understanding of factors that may inform the modeling process in

2.1 Animal Physiology

This section summarizes key concepts in animal physiology pertaining to heat stress. Unless explicitly indicated otherwise, the review from Citation: Kadzere et al., 2002 Kadzere, C., Murphy, M., Silanikove, N. & Maltz, E. (2002). Heat stress in lactating dairy cows: A review. , 77(1). 59–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-6226(01)00330-X serves as the source of information for this section and its subsequent subsections. We discuss some aspects of the cow physiology to better understand the complex heat-related interactions between the animal \(G\) and the environment \(E\). Moreover, the section highlights physiological arguments, why we might expect different heat stress responses for different breeds.

Heat Stress in Dairy Cows Heat stress is the collective impact of high temperatures compelling adjustments from sub-cellular to the whole animal level in order to avoid a physiological dysfunction and adapt better to the current environment.

As a homothermal, the cow must maintain a thermal equilibrium with the environment to regulate the biochemical reactions and physiological processes. The environmental factors include air temperature, air movement, humidity, as well as radiation. When cows fail to balance their body temperature within their thermoneutral zone and keep it in physiological homeostasis, they will experience hyperthermia, which may lead to death. The main characteristics of heat stress, independent of any effects of feed intake, are elevated respiration rates, increased rectal temperatures, an impaired metabolism, reduced growth and lactation, as well as poor reproductive performance.

2.1.1 Thermoregulation

Heat Increment The heat production in the dairy cow serves to maintain equilibrium with heat dissipation mechanisms and is controlled by the nervous system, endocrine system, appetite, digestion, respiratory enzymes as well as protein synthesis. Factors affecting the heat production intensity are the ambient temperature, hormone concentrations such as growth hormones, body size, breed, fodder and water availability. Heat increment is the increase in body heat production resulting from digestion, heat absorption, and the metabolism of nutrients activated through feed intake. Large amounts of feed intake generate significant metabolic heat. Moreover, an increased milk production relates to a raised heat increment. The heat increment during lactogenesis depends on the fodder quality and quantity. The milk production capacity also depends on the cow size. The latter is linked to the size of their gastrointestinal tracts, which have bigger digestion capacity in larger cows. This increased capacity results in a higher substrate availability for milk production.

Heat Dissipation Dairy cows lose heat through factors such as sweating, changes in environmental temperature, changes in the radiating surface, air flow changes, or convection. The amount of radiant heat a cow absorbs is influenced by the environmental temperature and its coat color. Dark-coated cows, for instance, generally absorb more heat than those with lighter brown coats. Cows can release metabolic heat through evaporative cooling, wherein water absorbs heat from the cow’s surface. The degree of heat loss through evaporation rises with increasing ambient temperatures. Additionally, convection serves as a method for heat dissipation when cooler air circulates around the warmer body, absorbing heat which is then carried away. However, if the surrounding air is warmer than the cow’s skin, heat is instead transferred into the animal’s body. Conductive transfer, another form of heat exchange, happens when the cow is in direct contact with another surface or entity. Unlike convection, which entails the movement of the subject, conduction involves heat transfer without the displacement of the subject. Conduction becomes pertinent when a cow is lying down, thus selecting appropriate ground surfaces or bedding materials is important for both animal welfare and strategies to mitigate heat stress.

Thermoneutrality Overall, the maintenance of thermoneutrality requires an equilibrium between heat gains and heat losses with the environment. This can be stated with the following heat balance equation \(M = \pm K \pm C \pm R + EV\), where \(M\) is the metabolic heat production, \(K\) is the heat exchanged by conduction, \(C\) by convection, \(R\) by radiation, and \(EV\) by evaporation. Generally, the thermoregulatory response of dairy cows may have changed over time since breeding strategies promote a genetic selection for an increased milk production (c.f. Figure 3.2).

Heat Stress When a cow absorbs more heat than it can dissipate, it experiences heat stress. Factors such as environmental conditions and specific animal traits such as age, breed, sex, metabolic state, coat condition, nutrition, and health status contribute to heat stress. For instance, Jersey and Holstein cows have varying rates of heat production and dissipation, which could be attributed to differences in body size. Additionally, performance indicators such as productivity, growth, and fertility are other factors influencing heat stress. These aspects are also affected by the type of housing, geographic location, the efficiency of ventilation systems, and the cow’s social rank within the herd. Generally, high-producing dairy cows are more affected because the thermoneutral zone shifts to a lower temperature range with a higher milk production, feed intake, and metabolic heat production (Citation: Gantner et al., 2017 Gantner, V., Bobic, T., Gantner, R., Gregic, M., Kuterovac, K., Novakovic, J. & Potocnik, K. (2017). Differences in response to heat stress due to production level and breed of dairy cows. , 61(9). 1675–1685. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-017-1348-7 ; Citation: Tapki & , 2006 Tapki, I. & Sahin, A. (2006). Comparison of the thermoregulatory behaviours of low and high producing dairy cows in a hot environment. , 99(1). 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2005.10.003 ).

Regulation Mechanism

Within the thermoneutral zone (TNZ), heat production is kept to a minimum under typical body temperatures, ensuring optimal physiological performance and maximum productivity. The lower limit of the TNZ is known as the lower critical temperature (LCT) and the upper limit as the upper critical temperature (UCT). For dairy cows, the TNZ spans about 5-25°C, with a UCT ranging from approximately 25-26°C

(Citation: Becker

et al., 2020

Becker,

C.,

Collier,

R. & Stone,

A.

(2020).

Invited review: Physiological and behavioral effects of heat stress in dairy cows.

, 103(8). 6751–6770.

https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2019-17929

). If the surrounding temperature falls below the LCT, the cow must elevate its heat production to maintain thermal balance. Between the LCT and UCT, the cow sustains its body temperature. An example reported LCT range is -17° to -30°C

(Citation: Kadzere

et al., 2002

Kadzere,

C.,

Murphy,

M.,

Silanikove,

N. & Maltz,

E.

(2002).

Heat stress in lactating dairy cows: A review.

, 77(1). 59–91.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-6226(01)00330-X

; Citation: Bryant

et al., 2007

Bryant,

J.,

López‐Villalobos,

N.,

Pryce,

J.,

Holmes,

C. & Johnson,

D.

(2007).

Quantifying the effect of thermal environment on production traits in three breeds of dairy cattle in New Zealand.

, 50(3). 327–338.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00288230709510301

). However, as the ambient temperature rises within the TNZ, evaporative heat loss diminishes, which is counteracted by vasodilation and increased water evaporation. Upon reaching the UCT, heat production rises due to inadequate evaporative cooling. When thermal stress exceeds the evaporative loss capacity, the cow may enter a state of hyperthermia. The specific values for LCT and UCT are influenced by factors such as age, species, breed, feed intake, diet composition, tissue and external insulation, as well as animal behavior.

Heat Stress Response Thermal sweating is a common response to heat stress. It plays a role in evaporative cooling and occurs when ambient temperatures rise, reducing the temperature gradient with the animal’s body. An increase in sweating is positively correlated with enhanced blood flow to the cow’s skin, and sweat rates can vary among different breeds. Breed variations influence how respiration rates respond to elevated temperatures; for example, Jersey cows often display higher respiration rates compared to Holsteins, suggesting better heat dissipation in Holsteins. Rising relative humidity during heat stress can result in decreased respiration rates, increased surface evaporation, raised rectal temperatures, reduced feed intake, and diminished milk production. Short-term heat exposure reduces heart rate as a stress response, though this effect diminishes with long-term exposure. Dairy cows under heat stress show reduced growth hormone levels because metabolic heat production must be lowered. High temperatures may enhance digestive efficiency due to prolonged feed retention and decreased dry matter intake.

To manage heat stress, dairy farmers employ protective measures, breeding strategies, and dietary adjustments. Quantifying the direct impact of environmental conditions on milk production is complex due to intricate interdependencies such as farm management. Nonetheless, research consistently shows a negative relationship between heat stress and milk output, including volume, fat, and protein content. Table 2.1 lists the expected effects on selected dairy performance metrics for lactating dairy cows.

| Variable | Effect | References |

|---|---|---|

| Milk | Decrease | Citation: Ahmed et al., 2022 Ahmed, H., Tamminen, L. & Emanuelson, U. (2022). Temperature, productivity, and heat tolerance: Evidence from Swedish dairy production. , 175(1-2). 10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-022-03461-5 ; Citation: Gisbert-Queral et al., 2021 Gisbert-Queral, M., Henningsen, A., Markussen, B., Niles, M., Kebreab, E., Rigden, A. & Mueller, N. (2021). Climate impacts and adaptation in US dairy systems 1981–2018. , 2(11). 894–901. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-021-00372-z |

| Fat | no effect\(^*\) Decrease\(\dag\) | Citation: Vroege

et al., 2023

Vroege,

W.,

Dalhaus,

T.,

Wauters,

E. & Finger,

R.

(2023).

Effects of extreme heat on milk quantity and quality.

, 210. 103731.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2023.103731

\(^*\) Citation: Moore et al., 2023 Moore, S., Costa, A., Penasa, M., Callegaro, S. & De Marchi, M. (2023). How heat stress conditions affect milk yield, composition, and price in Italian Holstein herds. , 106(6). 4042–4058. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2022-22640 \(^\dag\), Citation: Vinet et al., 2023 Vinet, A., Mattalia, S., Vallée, R., Bertrand, C., Cuyabano, B. & Boichard, D. (2023). Estimation of genotype by temperature-humidity index interactions on milk production and udder health traits in Montbeliarde cows. , 55. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12711-023-00779-1 \(^\dag\) |

| Protein | Decrease | Citation: Gao et al., 2017 Gao, S., Guo, J., Quan, S., Nan, X., Fernandez, M., Baumgard, L. & Bu, D. (2017). The effects of heat stress on protein metabolism in lactating Holstein cows. , 100(6). 5040–5049. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2016-11913 ; Citation: Vinet et al., 2023 Vinet, A., Mattalia, S., Vallée, R., Bertrand, C., Cuyabano, B. & Boichard, D. (2023). Estimation of genotype by temperature-humidity index interactions on milk production and udder health traits in Montbeliarde cows. , 55. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12711-023-00779-1 |

| SCC | Increase | Citation: Hammami et al., 2013 Hammami, H., Bormann, J., M’hamdi, N., Montaldo, H. & Gengler, N. (2013). Evaluation of heat stress effects on production traits and somatic cell score of Holsteins in a temperate environment. , 96(3). 1844–1855. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2012-5947 ; Citation: Lievaart et al., 2007 Lievaart, J., Barkema, H., Kremer, W., Broek, J., Verheijden, J. & Heesterbeek, J. (2007). Effect of Herd Characteristics, Management Practices, and Season on Different Categories of the Herd Somatic Cell Count. , 90(9). 4137–4144. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2006-847 |

| MUN | Increase | Citation: Gao et al., 2017 Gao, S., Guo, J., Quan, S., Nan, X., Fernandez, M., Baumgard, L. & Bu, D. (2017). The effects of heat stress on protein metabolism in lactating Holstein cows. , 100(6). 5040–5049. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2016-11913 |

| BHB | Increase | Citation: Stefanska et al., 2024 Stefanska, B., Sobolewska, P., Fievez, V., Pruszynska-Oszmałek, E., Purwin, C. & Nowak, W. (2024). The effect of heat stress on performance, fertility, and adipokines involved in regulating systemic immune response during lipolysis of early lactating dairy cows. , 107(4). 2111–2128. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2023-23804 |

| Lactose | no effect\(^*\) Increase\(^\dag\) | Citation: Kadzere

et al., 2002

Kadzere,

C.,

Murphy,

M.,

Silanikove,

N. & Maltz,

E.

(2002).

Heat stress in lactating dairy cows: A review.

, 77(1). 59–91.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-6226(01)00330-X

\(^*\) Citation: Moore et al., 2023 Moore, S., Costa, A., Penasa, M., Callegaro, S. & De Marchi, M. (2023). How heat stress conditions affect milk yield, composition, and price in Italian Holstein herds. , 106(6). 4042–4058. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2022-22640 \(^\dag\) |

| Citrate | Increase | Citation: Tian et al., 2016 Tian, H., Zheng, N., Wang, W., Cheng, J., Li, S., Zhang, Y. & Wang, J. (2016). Integrated Metabolomics Study of the Milk of Heat-stressed Lactating Dairy Cows. , 6(1). 24208. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep24208 |

| Aceton | Increase | Citation: Tian et al., 2016 Tian, H., Zheng, N., Wang, W., Cheng, J., Li, S., Zhang, Y. & Wang, J. (2016). Integrated Metabolomics Study of the Milk of Heat-stressed Lactating Dairy Cows. , 6(1). 24208. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep24208 |

Adaptation Dairy cows, akin to other homeothermic animals, have physiological processes to maintain their body temperature over a spectrum of environmental temperatures. The capacity to adapt to changing environmental conditions differs among species and breeds. For example, in an experiment with high-yielding cows that perform best in temperate climates, relocating them to tropical areas leads to reduced milk yield. Breeds that are native to tropical climates exhibit unique traits like decreased feed consumption, lower metabolism, improved heat release due to greater body surface areas, and either more sweat glands or shorter hair, assisting in transferring heat from the body’s center to the skin and environment. Research on heat stress indicates that Holsteins show more significant drops in milk and protein output than Jerseys under such conditions. The effects of adaptation diminish when exposure to heat stress lasts for several weeks. Moreover, dairy cows show a dual-phase daily cycle, with rising body temperatures from midnight to early morning and again from afternoon to evening. Lowering nighttime temperatures can counteract high daytime temperatures, offering some protection (Citation: Araki et al., 1987 Araki, C., Nakamura, R. & Kam, L. (1987). Diurnal temperature sensitivity of dairy cattle in a naturally cycling environment. , 12(1). 23–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-4565(87)90019-2 ). However, this protection is lost if nighttime temperatures remain elevated. Typically, these adaptation mechanisms can sustain regular productivity in warm climates. Even high-milk-producing cows can adapt during warm summer periods as they slowly acclimate to warmer weather. Nonetheless, sudden and extended extreme heat reduces the likelihood of adaptation and heightens the exposure to heat stress (Citation: Vroege et al., 2023 Vroege, W., Dalhaus, T., Wauters, E. & Finger, R. (2023). Effects of extreme heat on milk quantity and quality. , 210. 103731. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2023.103731 ).

2.1.2 Temperature Humidity Index

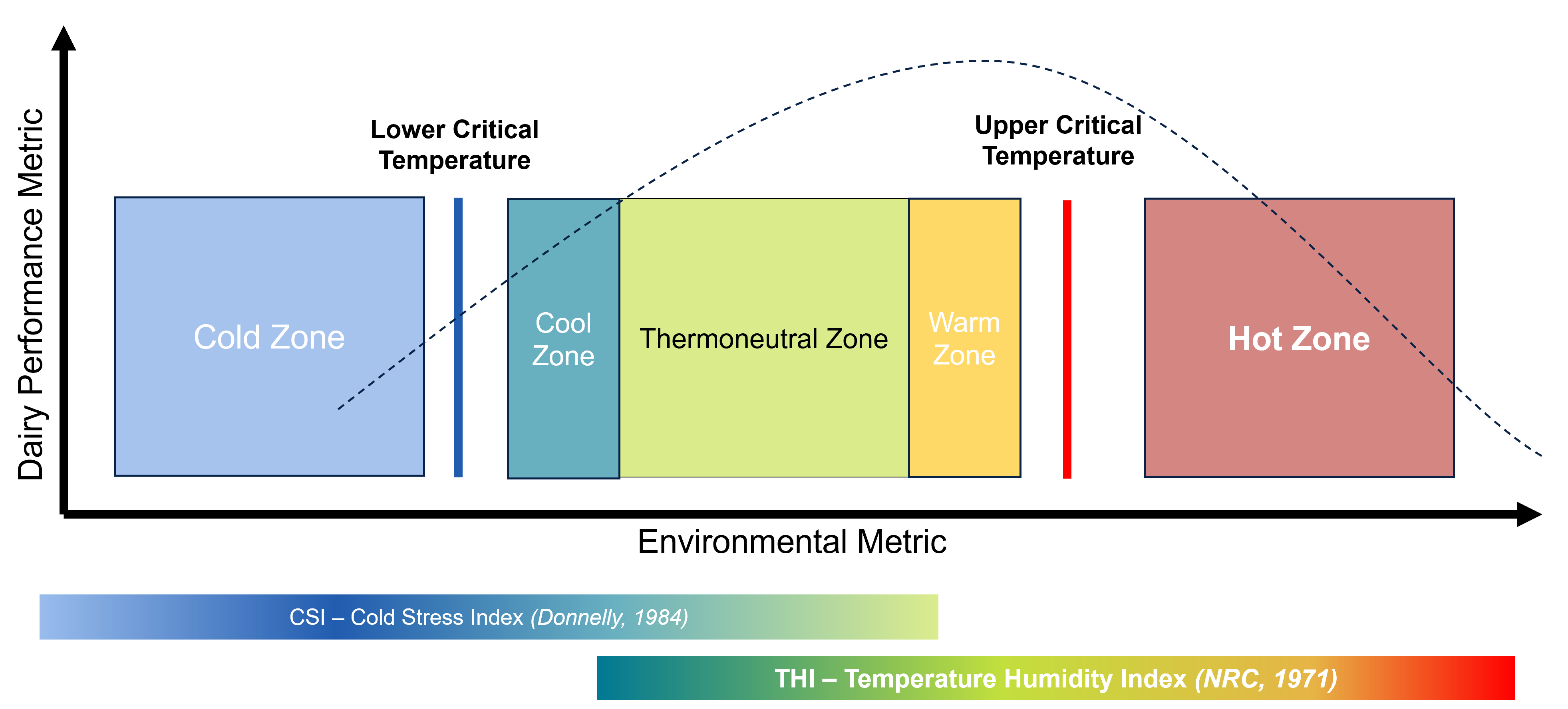

The Temperature Humidity Index (THI) is a metric to indicate the thermal climatic conditions with temperature and relative humidity. It is used as a proxy for heat stress levels and exposure, as depicted in Figure 2.1, with the goal of providing a more precise measure of environmental stress on cows than a single variable. The THI is a simple, comprehensive measure and is used as a tool for productivity insights, farm management decisions such as cooling systems or fodder adjustments, and animal welfare. The simplicity of the measure might be a reason for its wide acceptance in academia and industry.

However, disadvantages of the THI include its limitation to two variables, whereas other environmental factors such as radiation, wind speed, and precipitation also affect the thermal balance of dairy cows, as discussed in Section 2.1.1. Moreover, THI is not standardized

(Citation: Moore

et al., 2023

Moore,

S.,

Costa,

A.,

Penasa,

M.,

Callegaro,

S. & De Marchi,

M.

(2023).

How heat stress conditions affect milk yield, composition, and price in Italian Holstein herds.

, 106(6). 4042–4058.

https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2022-22640

). Oftentimes, the THI is used with threshold values to determine whether a cow is exposed to heat stress. However, these may not globally apply and depend on the location and other factors such as cow breed. Each individual animal may have varying heat stress tolerances. Different THI formulas exist for different regions to accommodate climate and environmental heterogeneity

For the remainder of this work, we use the THI definition from (Citation: National Research Council, 1971 National Research Council (1971). A guide to environmental research on animals. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/20608 ):

where \(T\) is the air temperature in \([°C]\) and \(RH\) the relative humidity in \([\%]\). Figure A.1 provides a THI mapping of the temperature from 0-40°C and the relative humidity from 0-100%.

2.2 Modelling Heat Stress Across Breeds

The preceding Section 2.1 discusses the manner in which diverse physiological characteristics, potentially unique to specific dairy cow breeds, influence their responses to heat stress. We have only identified three studies that explore the impact of weather conditions on dairy cow breeds within commercial pasture-based agricultural systems. Table 2.2 provides a brief comparison between their work and ours. The subsequent subsection will provide brief summaries of their methodology.

| Study | Breeds | Records | Farms | Cows | Time | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citation: Bryant et al., 2007 Bryant, J., López‐Villalobos, N., Pryce, J., Holmes, C. & Johnson, D. (2007). Quantifying the effect of thermal environment on production traits in three breeds of dairy cattle in New Zealand. , 50(3). 327–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/00288230709510301 | Holstein NZ Jersey HF/NZJ | 65,905 | 496 | 19,201 | 1990-2002 | New Zealand |

| Citation: Gantner et al., 2017 Gantner, V., Bobic, T., Gantner, R., Gregic, M., Kuterovac, K., Novakovic, J. & Potocnik, K. (2017). Differences in response to heat stress due to production level and breed of dairy cows. , 61(9). 1675–1685. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-017-1348-7 | Holstein Simmental | 1,070,554 1,300,683 | 5,679 8,827 | 70,135 86,013 | 2005-2012 | Croatia |

| Citation: Ahmed et al., 2022 Ahmed, H., Tamminen, L. & Emanuelson, U. (2022). Temperature, productivity, and heat tolerance: Evidence from Swedish dairy production. , 175(1-2). 10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-022-03461-5 | SE Holstein SE Red SH/SRB Other | 2,893,367 1,279,758 417,312 973,729 | 1,435 | ? | 2016-2019 | Sweden |

| Our work (2024) | Holstein Brown Swiss Original Braunvieh Simmental Swiss Fleckvieh Jersey | 27,536,089 56,695,597 4,996,060 8,731,876 31,484,784 734,685 | 24,963 26,585 18,613 19,411 27,392 4,302 | 971,198 1,719,156 149,478 299,698 1,038,291 23,675 | 1985-2023 1982-2023 1982-2023 1984-2023 1984-2023 1998-2023 | Switzerland |

2.2.1 Cow-Level Milk Yields Across Breeds (New Zealand)

Citation: Bryant et al., 2007 Bryant, J., López‐Villalobos, N., Pryce, J., Holmes, C. & Johnson, D. (2007). Quantifying the effect of thermal environment on production traits in three breeds of dairy cattle in New Zealand. , 50(3). 327–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/00288230709510301 propose a mixed model to quantify effects of the thermal environment across three breeds in New Zealand. Their focus is on heat stress as well as cold stress. Hence, they work with two environmental indices: the Temperature Humidity Index (THI) and the Cold Stress Index (CSI), as depicted in Figure 2.1. The study utilizes data provided by a corporation managing over 400 herds distributed across various regions of New Zealand. The sample set is restricted to first-lactation spring-calving animals exclusively.

Let \(\mathcal{H}\) denote the set of individual herds or farms, \(\mathcal{Y}\) the years for which data is available, \(\mathcal{B}\) the breeds under examination, and \(\mathcal{D}\) the test days considered. The dependent variables employed in this analysis include daily milk yield, as well as daily fat and protein concentrations. The model is defined as:

where:

- \(H_i\) is the fixed class effect for herd \(i \in \mathcal{H}\),

- \(Y_j\) the fixed class effect for year \(j \in \mathcal{Y}\),

- \(B_k\) the fixed class effect for breed \(k \in \mathcal{B}\),

- \(a_{i,j,k}\) the age of the cow at calving in months,

- \(d_{i,j,k}\) the parturition date deviation from the herd-year parturition date,

- \(t_{i,j,k,l}\) the days in milk for test day \(t\),

- \(x_{i,j,l}\) the 3-day average of the environmental index,

- \(c_{i,j,k}\) the annual random permanent effect of cows in herd \(i\) and year \(j\) for breed \(k\),

- \(\epsilon_{i,j,k,l}\) is the error term.

Accordingly, \(b_1\) and \(b_2\) are the age and parturition coefficients, \(\alpha_n\) are the Legendre polynomial coefficients measuring time effects with respect to days in milk, and \(\gamma_o\) measures the effect of the environmental index separately for each breed.

Limitations The effect of THI and CSI is modeled as an inverse parabola, which introduces a preliminary assumption about the non-linear effect of THI.

2.2.2 Cow-Level Milk Yields Across Breeds (Croatia)

Citation: Gantner et al., 2017 Gantner, V., Bobic, T., Gantner, R., Gregic, M., Kuterovac, K., Novakovic, J. & Potocnik, K. (2017). Differences in response to heat stress due to production level and breed of dairy cows. , 61(9). 1675–1685. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-017-1348-7 analyze the impact of THI on daily milk yield and somatic cell count in Croatia using a mixed model approach. Both breeds are split into high and low production levels based on their daily milk yield. A fixed-effect regression is executed for each combination of integer THI values, breed, and production level. The model accounts for effects such as days in milk, calving seasons, age at calving, region, and a binary heat stress indicator. To evaluate statistical significance, the authors compute the difference in mean square scores for each THI category and test for significance using Scheffe’s method.

Limitations The method does not account for the non-linear effects of THI on dairy cows. The authors use a mixed model but do not declare random effects. Moreover, critical THI levels are assumed to be within a range of 68 to 78.

2.2.3 Farm-Level and Cow-Level Milk Yields Across Breeds (Sweden)

Citation: Ahmed et al., 2022 Ahmed, H., Tamminen, L. & Emanuelson, U. (2022). Temperature, productivity, and heat tolerance: Evidence from Swedish dairy production. , 175(1-2). 10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-022-03461-5 employ several modeling approaches. One approach assesses the impact of temperature on average dairy production at the farm level, incorporating temperature as a non-linear smooth function. This methodology is considered more robust than the methods described in Section 2.2.1 and Section 2.2.2 since it allows for unrestricted non-linear temperature effects. The second approach utilizes a linear model with animal-level data to determine whether diversifying a herd with different breeds can serve as a strategy for mitigating heat stress.

Milk Performance Estimation

The authors use Generalized Additive Models (GAMs) to estimate the relationship between weather and milk performance variables. The dependent variables are the average milk produced per cow \([kg/day]\), average energy-corrected milk (ECM) produced per cow \([kg/day]\), and bulk milk somatic cell counts (BMSCC) \([cells/ml]\).

The penalized spline regression is:

where:

- \(i \in \mathcal{I}\) represents farms,

- \(t \in \mathcal{T}\) represents years,

- \(s \in \mathcal{S} =\) {Winter (December–February), Spring (March–May), Summer (June–August), Autumn (September–November)} represents seasons within a year,

- \(X_{i,s,t}\) accounts for first- and second-order effects of humidity and precipitation on temperature,

- \(\mu_{i,s}\) controls for unobserved farm characteristics and farm-specific seasonality,

- \(\epsilon_{i,s,t}\) is the error term,

- \(f_j\) are the non-parametric polynomial smooth functions estimated using a penalized log-likelihood method.

Breed Diversification

The authors also examine breed diversification as a heat stress adaptation measure. In this case, farms are defined in \(\mathcal{J}\) and cows in \(\mathcal{I}\).

Let \(\textit{Hw}_{j,s,t}\) be a heatwave indicator variable: \( \mathbf{1}\left (\bigwedge_{\tau=t-\delta}^{t} (\textit{Temp}_{j,\tau} \geq T)\right ) \) which equals 1 if the temperature on farm \(j\) has exceeded a threshold \(T\) for the past \(\delta\) days. The authors set \(\delta=6\) (covering the past week of the milk recording day) and \(T=25\)°C. The set \(\mathcal{M} = \{\text{SH, SRB, SH/SRB, Others}\}\) represents available breeds, where SH is Swedish Holstein, SRB is Swedish Red, and SH/SRB is a mixed breed.

The following regression incorporates the breeds:

where:

- \(i \in \mathcal{I}\), \(j \in \mathcal{J}\), \(t \in \mathcal{T}\), and \(s \in \mathcal{S}\),

- \(\alpha_m\) captures the effect of each breed \(m\) on milk production,

- \(\delta_m\) reflects the effect of breed \(m\) on milk production during a heatwave,

- \(\theta_{j,s}\) represents farm-level seasonal fixed effects,

- \(X_{i,j,s,t}\) includes farm-level weather controls and cow control variables such as days in milk and parity.

2.3 Evolution of the Swiss Dairy Market

Our study spans from 1982 to 2023. Switzerland’s dairy industry is a structured and regulated market, currently the most significant sector of Swiss agriculture. This section focuses on policy interventions affecting dairy cow husbandry and their implications for milk production. The policy interventions are summarized in Table 2.3.

| Policy | Description | Enactment | Expiration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Milk quotas | Limits production, penalizes excess | 1977 | 2009 |

| RAUS | Free-range production system | 1993 | — |

| BTS | Free-stall barns | 1996 | — |

| Milk price supplement | Cheese production, silage-free milk | 1999 | — |

| Grassland-based feeding | Less concentrate | 2014 | — |

| Commercial milk support | Export loss compensation | 2019 | — |

| Pasture payment | Ample outdoor access | 2023 | — |

| Cow longevity | Optimize longevity | 2024 | — |

1950-1990: Protective Years Following World War II, despite prevailing liberal economic policies, the Swiss agricultural sector is characterized by price guarantees, sales commitments, and tariffs, particularly in dairy production (Citation: Huber et al., 2023 Huber, R., Benni, N. & Finger, R. (2023). Lessons learned and policy implications from 20 years of Swiss agricultural policy reforms: A review of policy evaluations. https://doi.org/10.36253/bae-14214 ). The Agricultural Act of 1951 ensured prices covering production costs. Concurrently, economic rationalization led to fewer producers but higher milk production volumes.

By the 1970s, subsidies covering production costs rose to CHF 0.5 billion annually. To curb dairy production growth, farm-level milk production quotas were introduced in 1977, based on factors such as agricultural land area and farm location (Citation: Huber et al., 2023 Huber, R., Benni, N. & Finger, R. (2023). Lessons learned and policy implications from 20 years of Swiss agricultural policy reforms: A review of policy evaluations. https://doi.org/10.36253/bae-14214 ). Dairy production accounted for up to 54% of federal agricultural subsidies (Citation: Stadler, 2015 Stadler, H. (2015). Milchwirtschaft. . Retrieved from https://hls-dhs-dss.ch/de/articles/013952/2015-07-30/ ). This system led to surpluses sold on international markets, increasing federal financial obligations and prompting environmental concerns (Citation: Huber et al., 2023 Huber, R., Benni, N. & Finger, R. (2023). Lessons learned and policy implications from 20 years of Swiss agricultural policy reforms: A review of policy evaluations. https://doi.org/10.36253/bae-14214 ).

1990-2010: Decoupling and Liberalization In 1992, as a consequence of the previously mentioned national agricultural challenges and external pressure to comply with international standards, decoupled direct payments are instituted to support farmers independently of their production output and location, thus ensuring the maintenance of social and environmental standards. These direct payments comprise lump-sum area payments and ecological payments. The RAUS1 program is introduced in 1993 to encourage free-range production systems. The program mandates that dairy cows have access to pasture during the summer and to uncovered outdoor areas during the winter. In 1996, the BTS2 program is inaugurated, promoting animal-friendly housing systems such as free-stall barns. This action-based payment scheme is calculated annually per livestock unit, providing compensation for additional investment and workload.

A significant policy reform in 1999 links the eligibility for direct payments to the adherence to cross-compliance standards3. Furthermore, in 1999, price support measures for milk are abolished and tariffs are reduced to comply with international agreements. Concurrently, a milk price supplement payment for dairy milk processed into cheese and silage-free milk4 is established (Citation: Finger et al., 2017 Finger, R., Listorti, G. & Tonini, A. (2017). The Swiss payment for milk processed into cheese: Ex post and ex ante analysis. , 48(4). 437–448. https://doi.org/10.1111/agec.12345 ).

Since 2007, the cheese market between the European Union and Switzerland has been fully liberalized. Export subsidies and tariffs for cheese are progressively eliminated between 2002 and 2007. Shortly thereafter, in 2009, milk quotas are abolished, necessitating that milk producers and processors negotiate contracts to establish milk quantity and pricing.

2010-today: Ecology & Animal Welfare In 2014, a grassland-based milk and meat payment scheme5 is inaugurated. This action-oriented payment system compensates farmers based on the area of grassland cultivated. The policy is designed to promote sustainability, environmentally-friendly production systems, and a market-oriented approach to production (Citation: Mack et al., 2017 Mack, G., Heitkämper, K., Käufeler, B. & Möbius, S. (2017). Evaluation der beiträge für graslandbasierte milch- und fleischproduktion (GMF). Agroscope. Retrieved from https://ira.agroscope.ch/de-CH/publication/37016 ). In 2019, a compensation mechanism for commercial milk6 is introduced to mitigate the increased market pressures resulting from the termination of export payments. Producers of commercial milk receive compensation quantified per kilogram. In 2023, a pasture payment scheme7 is introduced as an alternative to the RAUS. This program is available to farms that provide ample access to uncovered outdoor areas and pastures for their cows. The initiative aims to lower ammonia emissions, encourage grassland-based production systems, and enhance animal welfare.

2.4 Bibliography

- Adhikari, Longman, Giambelluca, Lee & He (2022)

- Adhikari, M., Longman, R., Giambelluca, T., Lee, C. & He, Y. (2022). Climate change impacts shifting landscape of the dairy industry in Hawai‘i. , 6(2). txac064. https://doi.org/10.1093/tas/txac064

- Ahmed, Tamminen & Emanuelson (2022)

- Ahmed, H., Tamminen, L. & Emanuelson, U. (2022). Temperature, productivity, and heat tolerance: Evidence from Swedish dairy production. , 175(1-2). 10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-022-03461-5

- Araki, Nakamura & Kam (1987)

- Araki, C., Nakamura, R. & Kam, L. (1987). Diurnal temperature sensitivity of dairy cattle in a naturally cycling environment. , 12(1). 23–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-4565(87)90019-2

- Becker, Collier & Stone (2020)

- Becker, C., Collier, R. & Stone, A. (2020). Invited review: Physiological and behavioral effects of heat stress in dairy cows. , 103(8). 6751–6770. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2019-17929

- Bohmanova, Misztal & Cole (2007)

- Bohmanova, J., Misztal, I. & Cole, J. (2007). Temperature-Humidity Indices as Indicators of Milk Production Losses due to Heat Stress. , 90(4). 1947–1956. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2006-513

- Bryant, López‐Villalobos, Pryce, Holmes & Johnson (2007)

- Bryant, J., López‐Villalobos, N., Pryce, J., Holmes, C. & Johnson, D. (2007). Quantifying the effect of thermal environment on production traits in three breeds of dairy cattle in New Zealand. , 50(3). 327–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/00288230709510301

- Finger, Listorti & Tonini (2017)

- Finger, R., Listorti, G. & Tonini, A. (2017). The Swiss payment for milk processed into cheese: Ex post and ex ante analysis. , 48(4). 437–448. https://doi.org/10.1111/agec.12345

- Gantner, Bobic, Gantner, Gregic, Kuterovac, Novakovic & Potocnik (2017)

- Gantner, V., Bobic, T., Gantner, R., Gregic, M., Kuterovac, K., Novakovic, J. & Potocnik, K. (2017). Differences in response to heat stress due to production level and breed of dairy cows. , 61(9). 1675–1685. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-017-1348-7

- Gao, Guo, Quan, Nan, Fernandez, Baumgard & Bu (2017)

- Gao, S., Guo, J., Quan, S., Nan, X., Fernandez, M., Baumgard, L. & Bu, D. (2017). The effects of heat stress on protein metabolism in lactating Holstein cows. , 100(6). 5040–5049. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2016-11913

- Gisbert-Queral, Henningsen, Markussen, Niles, Kebreab, Rigden & Mueller (2021)

- Gisbert-Queral, M., Henningsen, A., Markussen, B., Niles, M., Kebreab, E., Rigden, A. & Mueller, N. (2021). Climate impacts and adaptation in US dairy systems 1981–2018. , 2(11). 894–901. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-021-00372-z

- Hammami, Bormann, M’hamdi, Montaldo & Gengler (2013)

- Hammami, H., Bormann, J., M’hamdi, N., Montaldo, H. & Gengler, N. (2013). Evaluation of heat stress effects on production traits and somatic cell score of Holsteins in a temperate environment. , 96(3). 1844–1855. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2012-5947

- Huber, Benni & Finger (2023)

- Huber, R., Benni, N. & Finger, R. (2023). Lessons learned and policy implications from 20 years of Swiss agricultural policy reforms: A review of policy evaluations. https://doi.org/10.36253/bae-14214

- Kadzere, Murphy, Silanikove & Maltz (2002)

- Kadzere, C., Murphy, M., Silanikove, N. & Maltz, E. (2002). Heat stress in lactating dairy cows: A review. , 77(1). 59–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-6226(01)00330-X

- Lievaart, Barkema, Kremer, Broek, Verheijden & Heesterbeek (2007)

- Lievaart, J., Barkema, H., Kremer, W., Broek, J., Verheijden, J. & Heesterbeek, J. (2007). Effect of Herd Characteristics, Management Practices, and Season on Different Categories of the Herd Somatic Cell Count. , 90(9). 4137–4144. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2006-847

- Mack, Heitkämper, Käufeler & Möbius (2017)

- Mack, G., Heitkämper, K., Käufeler, B. & Möbius, S. (2017). Evaluation der beiträge für graslandbasierte milch- und fleischproduktion (GMF). Agroscope. Retrieved from https://ira.agroscope.ch/de-CH/publication/37016

- Stadler (2015)

- Stadler, H. (2015). Milchwirtschaft. . Retrieved from https://hls-dhs-dss.ch/de/articles/013952/2015-07-30/

- Moore, Costa, Penasa, Callegaro & De Marchi (2023)

- Moore, S., Costa, A., Penasa, M., Callegaro, S. & De Marchi, M. (2023). How heat stress conditions affect milk yield, composition, and price in Italian Holstein herds. , 106(6). 4042–4058. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2022-22640

- National Research Council (1971)

- National Research Council (1971). A guide to environmental research on animals. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/20608

- Stefanska, Sobolewska, Fievez, Pruszynska-Oszmałek, Purwin & Nowak (2024)

- Stefanska, B., Sobolewska, P., Fievez, V., Pruszynska-Oszmałek, E., Purwin, C. & Nowak, W. (2024). The effect of heat stress on performance, fertility, and adipokines involved in regulating systemic immune response during lipolysis of early lactating dairy cows. , 107(4). 2111–2128. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2023-23804

- Tapki & Sahin (2006)

- Tapki, I. & Sahin, A. (2006). Comparison of the thermoregulatory behaviours of low and high producing dairy cows in a hot environment. , 99(1). 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2005.10.003

- Tian, Zheng, Wang, Cheng, Li, Zhang & Wang (2016)

- Tian, H., Zheng, N., Wang, W., Cheng, J., Li, S., Zhang, Y. & Wang, J. (2016). Integrated Metabolomics Study of the Milk of Heat-stressed Lactating Dairy Cows. , 6(1). 24208. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep24208

- Vinet, Mattalia, Vallée, Bertrand, Cuyabano & Boichard (2023)

- Vinet, A., Mattalia, S., Vallée, R., Bertrand, C., Cuyabano, B. & Boichard, D. (2023). Estimation of genotype by temperature-humidity index interactions on milk production and udder health traits in Montbeliarde cows. , 55. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12711-023-00779-1

- Vroege, Dalhaus, Wauters & Finger (2023)

- Vroege, W., Dalhaus, T., Wauters, E. & Finger, R. (2023). Effects of extreme heat on milk quantity and quality. , 210. 103731. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2023.103731